Last week while my husband, and I were watching July 4th fireworks, I decided I wanted to take a picture of him for Instagram. In general, he is mildly annoyed with the whole concept of social media, but he plays along with me with some semblance of patience. It was on the tenth or so take, that he started making disgruntled noises. He doesn’t mind taking one picture, but ten or twelve cross the line. He knows what I’m doing. I’m trying to get that one picture. The one that is Instagram-worthy. The one that makes us look at least slightly better than we actually do. I finally captured one and posted it. In the caption, I wrote something funny about how patient my husband is with my multiple attempts to get a photo right, but nothing about the experience sat well with me.

I noticed this kind of behavior in myself, but I also see it all around me, and not just taking multiple shots of one image, but of trying to record or capture entire memories. This week I am on vacation with my family, and of the stops on our extended road trip was to the World of Coca-Cola in Atlanta. Yesterday, as we explored the museum, I couldn’t help but notice how many people were recording and documenting each exhibit. Even in the places where we had been asked to put away our phones, people were watching the show through the lens of their phone screens. It seemed that it was more important to capture the moment than to live in it.

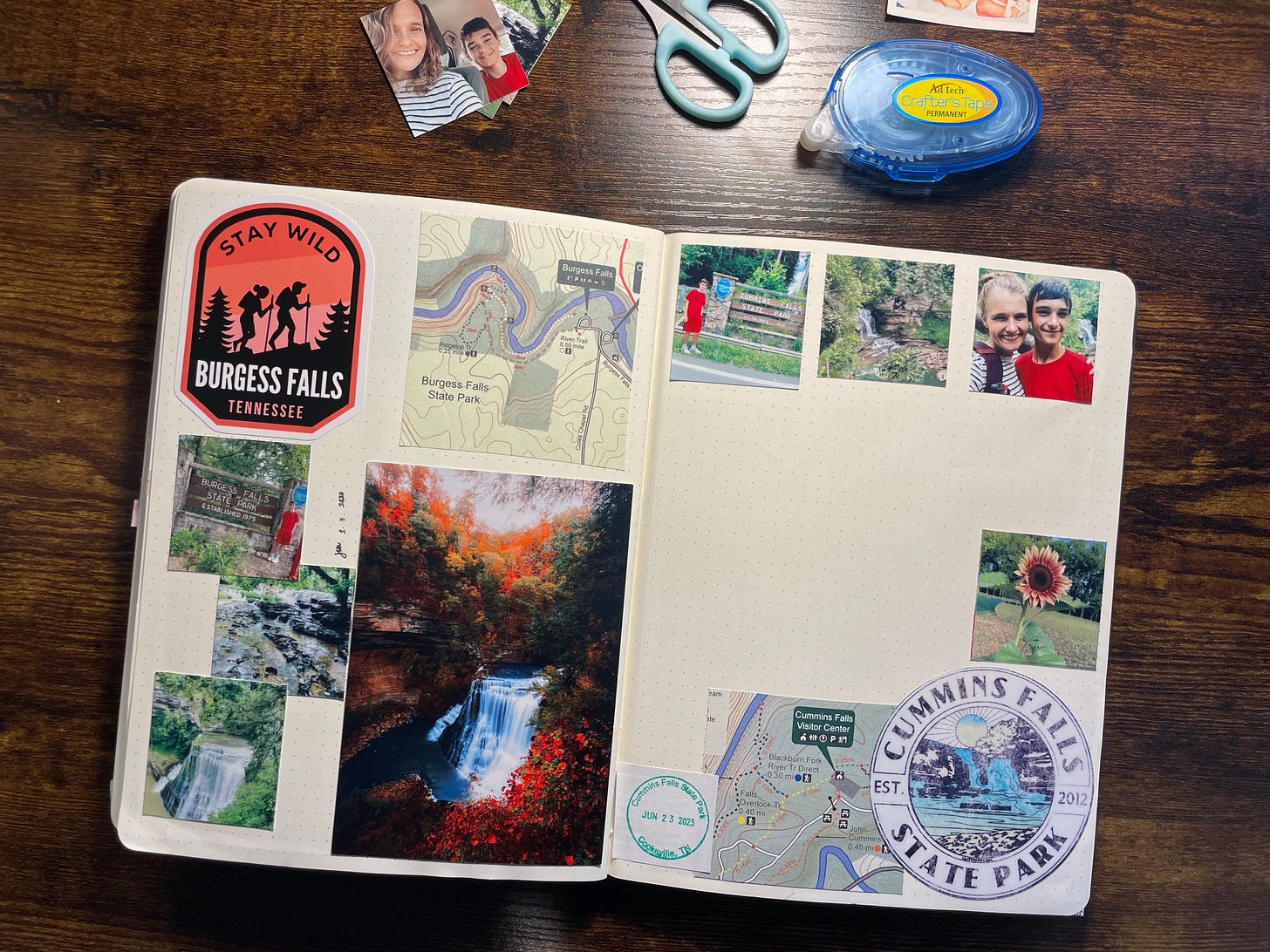

Since I posted last week about the time I spent outside with my son without my phone, I’ve been thinking a lot about memory and memory-keeping. I’ve told myself for years that social media apps like Instagram are about memory-keeping, but if that were true, my pictures wouldn’t really need to meet a certain standard of perfection, and I maybe wouldn’t need so many of them. Last year I started creative journaling as an alternative to social media for documenting memories, and I quickly realized that there is a stark difference between taking a picture for my journal and taking a picture for Instagram. Taking a picture for Instagram requires multiple tries and usually ends with somebody frustrated. Taking a picture for my journal is only requires one shot or maybe two if someones eyes are closed. I realized with great clarity, that taking pictures for Instagram is really not about memory-keeping, at least not for me. What I’m doing on Instagram is sharing my memories for (and maybe not even with) my perceived audience. I’m taking my own memory, shining it up, and posting it for others to see. That’s all fine, unless it actually impairs or distorts my own ability to make and keep my own memories.

In a similar way, I couldn’t help but wonder if the people that I saw documenting what seemed to be each and every moment at the Coke Museum were impacting their own memories of the event. Does recording an event and viewing it through an iPhone impair the memory? Do our attempts to keep picture and videos of cherished moments in our lives result in an outsourcing of memories to our phones? I can’t help but wonder.

With all this swirling in my head, I did a little research on the connection between social media and memory. Sure enough, I found an article in Time magazine article called “How Social Media is Hurting Your Memory” that cites a paper published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. The study looked at the ways in which we document our experiences can impair the actual forming of memories. The article examined both social media use as well as other ways we try to keep memories. Sure enough, they concluded that there was a memory deficit for some of the participants attempting to document an experience for social media:

“In a new paper published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, researchers showed that those who documented and shared their experiences on social media formed less precise memories of those events.”

It seems, though, that it’s not just as simple as documenting an event on social media that is to blame for memory impairment, but rather, our attempts to externalize the memory also have a negative impact on our ability to form memories:

“The researchers concluded that the likely culprit of the memory deficit was not purely social media, because even taking photos or writing experiential notes without publishing them showed the same effects. Just interrupting the experience didn’t seem to hurt…Instead, it was the act of externalizing their experience — that is, reproducing it in any form — that seemed to make them lose something of the original experience.”

The article goes on to discuss transitive memory and they way we decide what we story internally, and what can be stored elsewhere. When I take time to capture that perfect picture, or record the world’s oldest coke bottle. I am in my own way externalizing the memory, and in effect, impairing my own internal mechanism of memory attainment.

I want to make clear that I am not disparaging the use of social media or the use of cameras to take pictures and videos of important memories. Like the study demonstrates, it isn’t necessarily interrupting the moment to take the picture that impairs memory, but rather it is the attempt to recreate or reinvent the memory outside of yourself that is the problem. For me this means simply reminding myself that it is fine to get a picture to help aid my God-given memory, but the more time I spend trying to capture the memory, and the less time I spend actually living in the moment, the less of the experience I will take with me.

The memories that we store inside of us are where the magic is. If photographs can aid in our own internal memories then they benefit us. If they become the memory, they steal from us.

When we are young our memories may not seem as important, but as we get older, they become more and more valuable. As Jayber Crow reflected toward the end of his life:

“Back there at the beginning, as I see now, my life was all time and almost no memory. Though I knew early of death, it still seemed to be something that happened only to other people, and I stood in an unending river of time that would go on making the same changes and the same returns forever. And now, nearing the end, I see that my life is almost entirely memory and very little time” (p. 24).

And for me personally, there is a spiritual element to this as well. Some of my “memory keeping” over the years has been much more about putting a shiny gloss over my life than it has been about storing and/or remembering a memory. When I’m trying to get my kids to pose for the hundredth time, or when I’ve taken my husband to the border of bad mood just because I want us to look a certain way, I’m no longer trying to keep a memory. I’m trying to create an image, and that for me is the biggest danger. It is a pride issue in me, for sure, and one I have to consistently hand over to God. To be clear, I don’t think this is a problem for everyone, but I certainly think it exists more we care to admit.

I think at the heart of this is a desire to live fully and to be able to look back at our lives whether in the pages of our mind or the camera app on our phones, and say by the grace of God, my life was blessed. Whether we share our memories with thousands of others or we keep them tucked away in our hearts doesn’t matter as much as whether or not we lived them fully in the moments we have been given.

And one day when we find that we have more memories than time, I pray we will be rich with them.

This is so interesting! I’m taking a social media break/“digital detox” for a month and it took several days to get out of the “I’ve gotta share this on Instagram!” mentality 🙈😅 Now I don’t think it that often a week into this experiment. Thanks for sharing this angle about memory keeping! Never would’ve thought of this.

I wonder how the researchers determined that reproducing an experience in any form made the subjects lose something of the original experience. As a long time scrapbooker, I enjoy referring to the record of what I took away from an experience at the time. How can that be less original than some future interpretation of what has to become a hazier memory of the details over time? I guess much depends on whether you are recording your experience as it happened or recording an experience that you've orchestrated or edited.